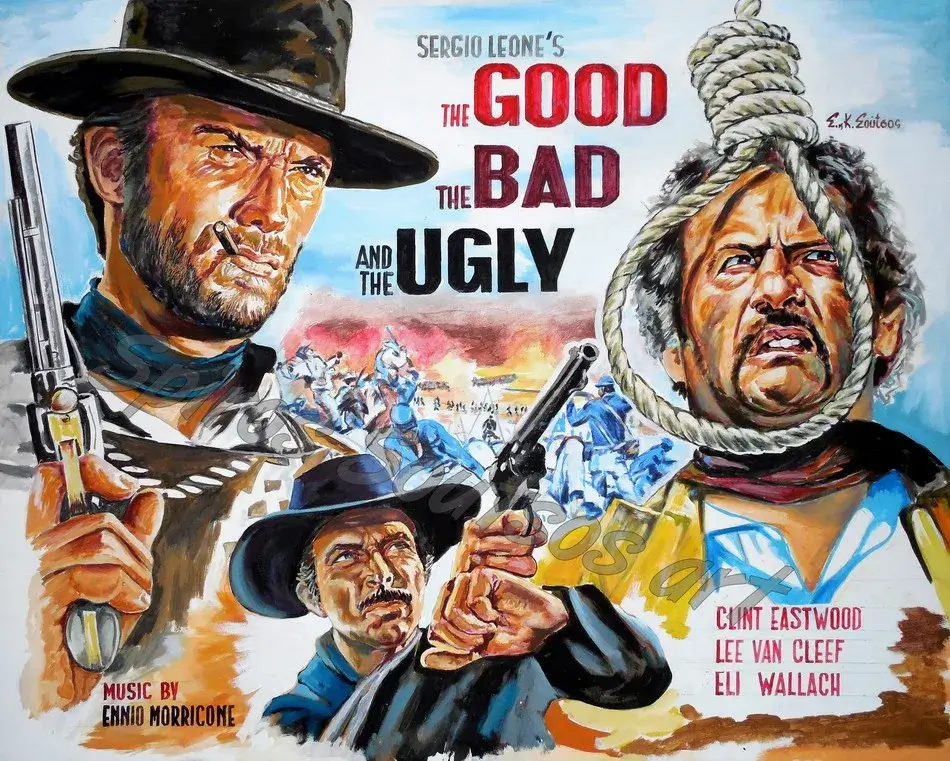

Sergio Leone’s For a Few Dollars More (1965) is not just a film—it’s a cornerstone of the spaghetti western genre, a cinematic triumph that builds on the raw foundation of A Fistful of Dollars and sets the stage for the grandeur of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly.

Released in 1965 as the middle chapter of the Dollars Trilogy, For a Few Dollars More (1965) sharpens its predecessor’s edge with a more intricate plot, deeper character development, and a score by Ennio Morricone that remains one of the most iconic in film history. Clint Eastwood returns as the stoic, poncho-clad bounty hunter Monco (often interpreted as the Man with No Name), joined by Lee Van Cleef as the steely-eyed Colonel Douglas Mortimer. Together, they elevate For a Few Dollars More (1965) into a timeless exploration of greed, revenge, and uneasy alliances, all wrapped in Leone’s signature visual poetry.

The story centers on Monco and Mortimer, two bounty hunters with clashing styles and motives, who form a tenuous partnership to hunt down El Indio (Gian Maria Volonté), a sadistic bandit fresh from a prison break. Monco is the quintessential drifter, motivated by the promise of reward money, while Mortimer’s pursuit is steeped in a personal tragedy revealed through haunting flashbacks involving a musical pocket watch. This contrast fuels the film’s emotional core, transforming For a Few Dollars More (1965) from a mere western into a layered character study.

Leone’s direction is nothing short of masterful—his use of wide-angle shots captures the desolate beauty of the Almerían desert, while his trademark close-ups of weathered faces and twitching trigger fingers ratchet up the suspense. The climactic showdown, underscored by Morricone’s chilling chimes and soaring strings, is a textbook example of how to craft a duel that’s as psychological as it is physical.

What makes For a Few Dollars More (1965) truly exceptional is its seamless fusion of style and substance. Eastwood’s minimalist performance—conveyed through squints and sparse dialogue—perfectly complements Van Cleef’s commanding presence, his sharp features and piercing gaze hinting at a lifetime of unspoken pain. Volonté, meanwhile, delivers a villain who’s both charismatic and unhinged, his maniacal laughter echoing through the film’s darker moments.

The supporting cast, including Klaus Kinski as a hunchbacked gunslinger, adds texture to an already rich tapestry. Leone’s pacing, slower and more deliberate than many American westerns of the era, allows the tension to simmer, culminating in a payoff that feels both inevitable and profoundly satisfying. Within the Dollars Trilogy, For a Few Dollars More (1965) occupies a sweet spot—lacking the bare-bones simplicity of the first film or the sprawling ambition of the third, it offers a tightly woven narrative that balances action with introspection.

For modern viewers, For a Few Dollars More (1965) remains a cinematic treasure worth revisiting or discovering anew. Its influence reverberates through decades of filmmaking, from Quentin Tarantino’s dialogue-driven standoffs to the brooding anti-heroes of contemporary action flicks. The availability of 4K restorations has breathed new life into its dusty landscapes and intricate costume details, making it a visual feast for today’s audiences. Beyond its technical merits, the film’s themes—loyalty tested by greed, justice tangled with vengeance—resonate as powerfully now as they did in 1965.

In a genre often reduced to clichés of cowboys and shootouts, For a Few Dollars More (1965) stands out as a work of art, proving that with a few dollars, a visionary director, and a stellar cast, you can create a legacy that endures.

Discover more from World of Movie

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.